The Evolution of the Port of Belém throughout the 17th Century

Concerned with the successes achieved by French colonisation in northeastern Brazil (the so-called Equinoctial France), the Portuguese Crown organised an expedition to conquer Maranhão. By express orders of King Philip II, the Portuguese attacked the French fortress of São Luís. On 3 November 1615, after four days of siege, they forced its garrison to surrender unconditionally. Following the victory, the Portuguese began organising new settlements in northern Brazil to prevent further foreign incursions.

Francisco Caldeira de Castelo Branco, former Captain-Major of the Captaincy of Rio Grande do Norte (1612–1614) and one of the members of the victorious expedition to Maranhão, was ordered to travel to what would become Pará to secure it for Portugal.

Departing from São Luís on 25 December 1615, with three vessels and a garrison of 150 soldiers, the expedition arrived at the Bay of Guajará on 12 January 1616. The landing took place on an elevated promontory, known to the Tupinambá Indians as “Mairi”, a fragment of terrace dominating the strategic confluence of the Pará and Guamá rivers, “inaccessible from the sea and defended on land by an extensive creek, which, originating in the Piri swamp, flowed into what is today the Ver-o-Peso dock.” There, Francisco Caldeira de Castelo Branco ordered the construction of a wooden palisade in the form of a small fort, named the Presépio de Belém, possibly in honour of the expedition’s departure from São Luís on Christmas Day. Within it, the first Portuguese colonial settlement in the Amazon developed, baptised by the Captain-Major as Feliz Lusitânia.

The first port of the new Portuguese colony, emerging alongside the arrival of Belém’s founder expedition, took the form of a modest anchorage on the left bank of the mouth of the Piri creek, at the foot of the terrace where the fort was located.

Soon, Feliz Lusitânia began to expand beyond the Presépio walls, with the appearance of the first streets. In 1627, a path was opened connecting the right bank of the Piri to the Church of Santo Antônio, known as Rua dos Mercadores (today Conselheiro João Alfredo), which became the central axis of Belém’s urban development throughout the 17th century. Ending at a square where, in 1640, the Mercedarians built their church, this path attracted a significant portion of the local inhabitants, including the first merchants, prompting the transfer of the main landing from the left to the right bank of the Piri, located between its mouth and the start of Rua dos Mercadores. Throughout the 17th century, this anchorage served as the city’s port, with ships arriving from Europe anchoring in the Bay of Guajará, in front of or north of the Piri’s mouth, while river vessels sought shelter at the mouth itself, which for a long time remained Belém’s true port, represented by a stone ramp.

At that time, the inhabitants of Feliz Lusitânia began searching for gold, which they imagined to be somewhere in the vast tropical forest, as numerous legends, feeding European imagination for centuries, portrayed the Amazon as a lost paradise abundant in riches, or even as the Garden of Eden.

However, this eagerness to explore the Amazon was driven less by the search for Paradise and more by the wealth offered by a new economic model in vogue in Europe after the discovery of the maritime route to the Indies in 1498: mercantilism, with its rapid and extraordinary profits derived from abundant natural resources, whether precious metals or extractive products. Although searches proved fruitless regarding metals, explorations revealed to the Portuguese other forest riches, the so-called “drogas do sertão”, which could be of plant origin—such as cocoa, clove, vanilla, indigo, cinnamon, parsley—or of animal origin—such as pirarucu, manatee, turtles, crabs, and the meat and hides of mammals like capybara and jaguar, among others. The importance of these products grew when the Portuguese realised that they equalled Eastern spices in quality, but offered a better final price, since the journey from Brazil to Portugal was shorter. In this way, these “drogas” represented the economic basis for controlling the region in this early period.

The 18th Century

Until 1750, Portugal’s policy in the Amazon did not result from a preconceived plan, since it was carried out according to the needs of the moment, accepting the region’s specific conditions.

With the accession of King José I to the Portuguese throne in 1750, and the appointment of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the future Marquis of Pombal, as Minister of Foreign Affairs, this state of affairs began to change. The powerful minister, in little time the de facto ruler of Portugal, imbued with Enlightenment and absolutist ideals, would vigorously address the economic problems confronting the new government: the Portuguese state needed to accumulate capital, and in response, Pombal aimed to establish a capitalist-style economy in the Amazon, although much of the region’s economy remained under the control of religious orders.

Thus, the Marquis of Pombal paid special attention to the region. He appointed a trusted man, his own brother Francisco Xavier de Mendonça Furtado, as Governor of Grão-Pará, responsible for implementing the new Amazon policy, which consisted essentially in exerting the Portuguese Crown’s power directly over the territory and its population, bypassing the missionaries. The Companhia Geral do Grão-Pará e Maranhão was then created, encouraging the export of the Captaincy’s production, resulting in an ever-increasing collection of “drogas” and the promotion of agriculture—particularly the cultivation of rice, coffee, and cocoa—and cattle ranching on Marajó Island. This policy sought to promote the region’s fullest exploitation, rationally utilising its resources. The aim was to consolidate Portuguese domination in the Amazon, with Belém as its base.

From the second half of the 18th century, continued exploration along the Amazon River, the mapping of its tributaries, the exploitation of its countless resources, and the clear understanding of the vast territorial extent under the Portuguese Crown’s control in northern Brazil, led both governors and the governed to acknowledge that a period of great prosperity had arrived for the Captaincy of Grão-Pará.

The 19th Century

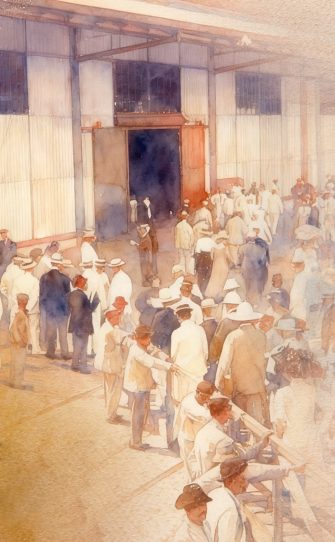

During the first half of the 19th century, Belém experienced significant commercial activity: large quantities of cocoa, coffee, cotton, cloves, leather, and timber were exported. However, by around 1839, the city demanded the construction of a port capable of meeting its needs, as until then there existed only a small stone quay located on the Bay of Guajará, between the Convent of Santo Antônio and Travessa das Gaivotas (today 1º de Março), and a ramp popularly known as the “stone bridge”, situated between the same street and Ver-o-Peso. The lack of a modern port led to the proliferation of wooden wharves along the Bay of Guajará, serving the navigation companies operating in the Amazon.

The expansion of river voyages inland also contributed to the need for a new port in Belém. These voyages began on 11 January 1853, with the first steamship trip of the Amazon Navigation and Trade Company, destined for São José do Rio Negro (now Manaus). This type of journey opened entirely new commercial prospects for Belém, encouraging the creation of numerous trading companies, such as the Upper Amazon River Company (1866) and the Paraense River Company (1867). With these inland voyages and the emergence of trading companies, Belém’s port traffic tripled: in 1840, 78 ships docked with a registered tonnage of 11,252; by 1880, 292 ships docked, with tonnage reaching 258,115.

However, the decisive impetus for constructing a new port came from rubber exports, which by the late 19th century had already reached very high levels.

The 20th Century

The process of nationalising the Port of Pará Company culminated with Decree-Law No. 2,147 of 27 April 1940, which created the Amazon Navigation and Port Administration Service (SNAPP), the body responsible for managing the Port of Belém. During its administration, SNAPP faced two major challenges: first, the effects of World War II, which caused a decline in exports, imports, and overall port activity; second, what António Rocha Penteado called the “lack of cargo,” which meant that only once between 1915 and 1965 did the Port of Belém’s movement exceed one million tons: “only a high-value commodity [such as rubber during the Port of Pará era], traded in a period of total scarcity of that same commodity elsewhere in the world, could sustain and stimulate such port traffic.”

Additionally, SNAPP failed to fulfil the task for which it was created, mainly because it inherited the crisis that had affected the Port of Pará. During its administration, the Port of Belém operated precariously, as channel access conditions were halved due to lack of funds for regular dredging; furthermore, its obsolete industrial infrastructure compromised both technical maintenance and port traffic. Due to these nearly insurmountable problems, SNAPP was abolished by Decree 61,600 on 6 September 1967. In its place, using the social capital formed with its assets, the Companhia Docas do Pará (CDP) was founded, tasked with “promoting the management of organised ports and terminals in Pará.”

The new company inherited from its predecessor what Antônio da Rocha Penteado described as an “import port,” since imports never fell below 50% [in the period 1957–1966] of the total tonnage handled at the time, even accounting for small-scale coastal trade. This highlighted the regional importance of the Port of Belém. Moreover, the company’s extensive direct administrative area, stretching from the mouth of the Oriboca River along the eastern coast of the Bay of Guajará to Mosqueiro Island—a total of 34 kilometres—posed additional challenges.

Therefore, the Companhia Docas do Pará faced a major task: the development of a complex port system, “which, in its interactions with land and sea, presents a series of situations requiring careful attention to better understand its problems.”

The “Port of Pará” Company

Based on the report of engineer Domingos Sérgio de Sabóia e Silva, the Federal Government opened a public tender for the construction of the new Port of Belém, which was won by João Augusto Cavallero and Frederico Bender on 15 November 1902.

When construction was about to begin, the concession was declared void, as the contractors had not signed the contract within the stipulated period. Consequently, a new tender was opened on 18 April 1906, this time won by American engineer Percival Farquhar.

Farquhar “was to build and organise the port from the mouth of the Oriboca River in Guamá to the tip of Mosqueiro (…), with the first section consisting of a 1,500-metre quay starting from the Ver-o-Peso Dock, equipped with the respective bollards, mooring devices, and stairways, and properly fitted with electric cranes, railway lines, and lighting.” Farquhar was also responsible for dredging the bay, constructing embankments, opening a 30-metre-wide street parallel to the quay, building warehouses, installing signalling buoys, and erecting the necessary administrative and inspection buildings. In return, he would receive a net rent equivalent to 6% of the capital invested in construction, the right to operate the first section of the works until 1973 and the second section until 1996, tax exemptions for importing construction materials, among other incentives.

To carry out the project, Farquhar organised the Port of Pará Company at the offices of Corporation Trust Co., in Portland, United States, on 7 September 1906. The Brazilian Government’s interest in the project, the guarantees offered for its feasibility, and the fact that Farquhar had obtained approval from the renowned firm S. Pearson & Sons ensured the participation of numerous investors and the capital necessary for this ambitious endeavour.

Farquhar and W. Pearson, the engineer responsible for the works, decided to begin constructing the port’s quay, placing large prefabricated concrete blocks along the bank and connecting them, while dredgers excavated the bay floor and reclaimed the land for warehouses and the grand avenue. On 2 October 1909, the first phase of the port was inaugurated: a 120-metre quay and a warehouse.

Construction continued at a rapid pace: by 1914, 1,869 metres of quay had been built; dredging moved 5,665,913 m³ of sand and mud, forming the future Castillos França boulevard embankment; 13 metal-structure warehouses, supplied by the French firm Schneider & Cie of Creusot, covering a total area of 27,700 m², were completed; 6,500 metres of railway tracks were laid; and 11 electric cranes were installed for cargo handling. The quay was illuminated by 2,200 electric lamps, and 30 buoys marked the port’s access channel.

However, from 1914 onwards, the depreciation of rubber, combined with the decrease in imports due to World War I and the subsequent contraction of foreign capital, caused the Port of Pará to enter a crisis, seeking a new agreement with the Federal Government regarding the continuation of works. Some second-section quay constructions were postponed until traffic needs demanded their completion, as were certain first-section works, such as the Customs House and the Post and Telegraph building. The crisis intensified between 1914 and 1920, when the company’s expenses increased by approximately 100%, all covered by the Federal Government, which became its main creditor. The situation reached such a point that the company’s shareholders appealed to the court in the U.S. state of Maine, where its headquarters were located, and succeeded in placing it under a commission’s intervention on 26 March 1915.

In 1921, the Brazilian government suspended payment of the company’s guarantees. The crisis persisted until 1940, when the company was obliged by decree to reimburse over 350,000 contos de réis to the Federal Government for quay fees collected above the 6% it was entitled to under the concession. “As the total received indirectly reached 354,934,381$ and the valuation of all company works and installations amounted to 307,013,984$, these were to serve as guarantees for the debt repayment.” Thus, in 1940, the Port of Pará Company came under the control of the Brazilian Federal Government.

The Port of Belém Today

The Port of Belém continues to be administered by the Companhia Docas do Pará (CDP), whose structure has changed considerably since its foundation in 1967, transforming into a holding company managing a total of ten ports and the Eastern Amazon and Tocantins-Araguaia waterways.

In 1999, CDP ports received 5,518 vessels, handling a total of 9,000,682 tonnes of cargo. At the Port of Belém, the main cargoes included timber (representing 55.87% of total cargo in 1999), black pepper, heart of palm, fish, shrimp, Brazil nuts, wheat, cement, and foodstuffs, totalling 796,477 tonnes.

Belém also hosts the Miramar Petrochemical Terminal, equipped for the loading and unloading of liquid fuels and up to 92 storage tanks, which handled 1,365,772 tonnes. The Port of Vila do Conde, in Barcarena, is the busiest port in the Amazon, handling products from the so-called Aluminium Complex, comprising ALBRÁS (aluminium) and ALUNORTE (alumina), totalling 5,809,041 tonnes in 1999. The Port of Macapá, inaugurated in 1982, experienced a major increase in cargo handling, mainly due to the creation of the Macapá and Santana Free Trade Zone. The Port of Santarém, inaugurated in 1974, specialises in agro-industrial and extractive cargoes. In addition to these five main ports, CDP manages the ports of Itaituba, Altamira, Marabá, Óbidos, and São Francisco, all river ports.

Today, CDP is committed to implementing the Port Modernisation Law, whose main goal is to reduce port operation costs and make Brazilian ports more efficient and competitive. Its activities have therefore been outsourced, a process that will also extend to the other ports under its management.